Research

Oct 20, 2025

Exercise as Medicine: Rethinking Healthcare Through Movement

Exercise as Medicine: Rethinking Healthcare Through Movement

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

Introduction

Across the world, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular illness, diabetes, cancer, and depression are rising faster than healthcare systems can contain them. Yet one of the most powerful, low-cost, and universally accessible treatments remains underused: movement itself. Regular physical activity prevents, manages, and reverses many of the conditions that shorten lives and strain economies. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, it is still prescribed far less often than pills or procedures. According to the British Heart Foundation, insufficient physical activity contributes to more than five million preventable deaths each year.

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

The Missing Prescription

Across the world’s clinics and hospitals, patients wait in search of relief from fatigue, pain, and the slow erosion of wellbeing that chronic illness brings. They leave with prescriptions for pills or procedures, but almost never with one for movement. This absence is more than an oversight; it’s a paradox at the heart of modern healthcare.

Physical inactivity now rivals smoking and poor diet as one of the leading causes of premature death, claiming millions of lives each year despite being entirely preventable. The idea that movement itself could serve as medicine remains peripheral in clinical practice, even as the evidence grows impossible to ignore.

Regular physical activity strengthens nearly every system of the human body. It improves cardiovascular function, enhances immune response, balances metabolism, sharpens cognition, and elevates mood. Exercise is both prevention and cure, capable of reducing the risk of more than 30 chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, several cancers, and dementia. Yet health systems continue to invest primarily in treating illness rather than cultivating health.

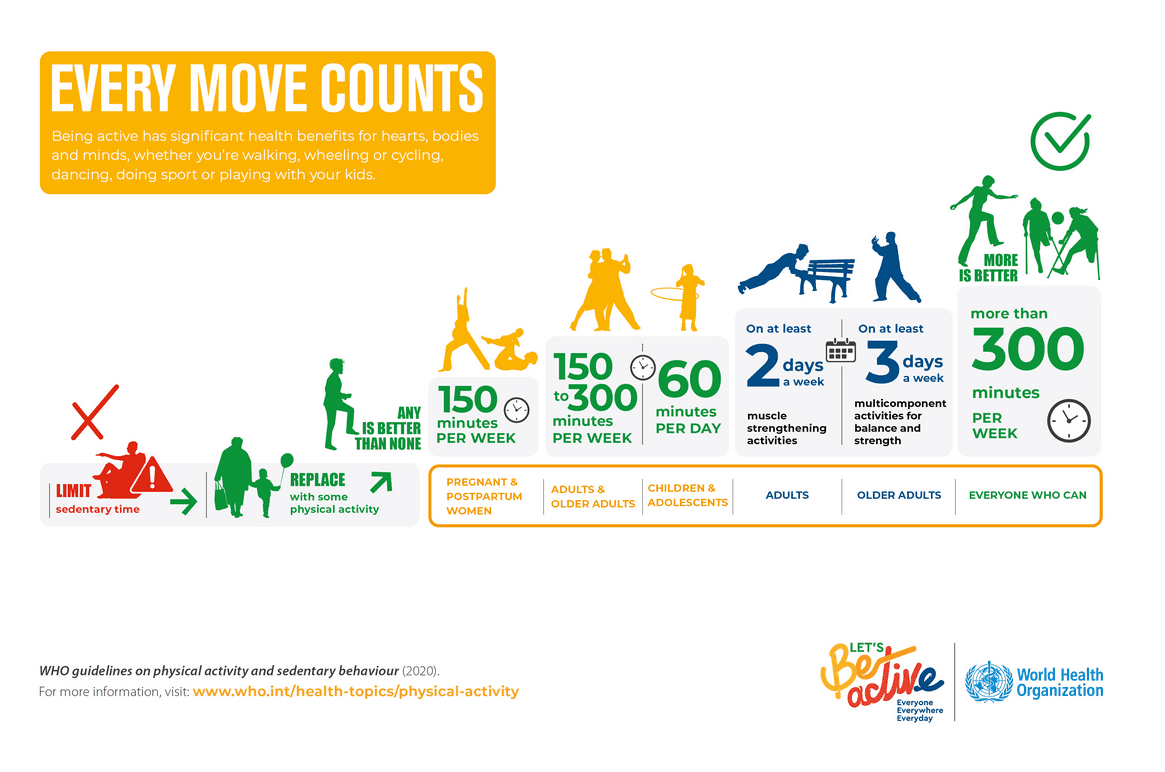

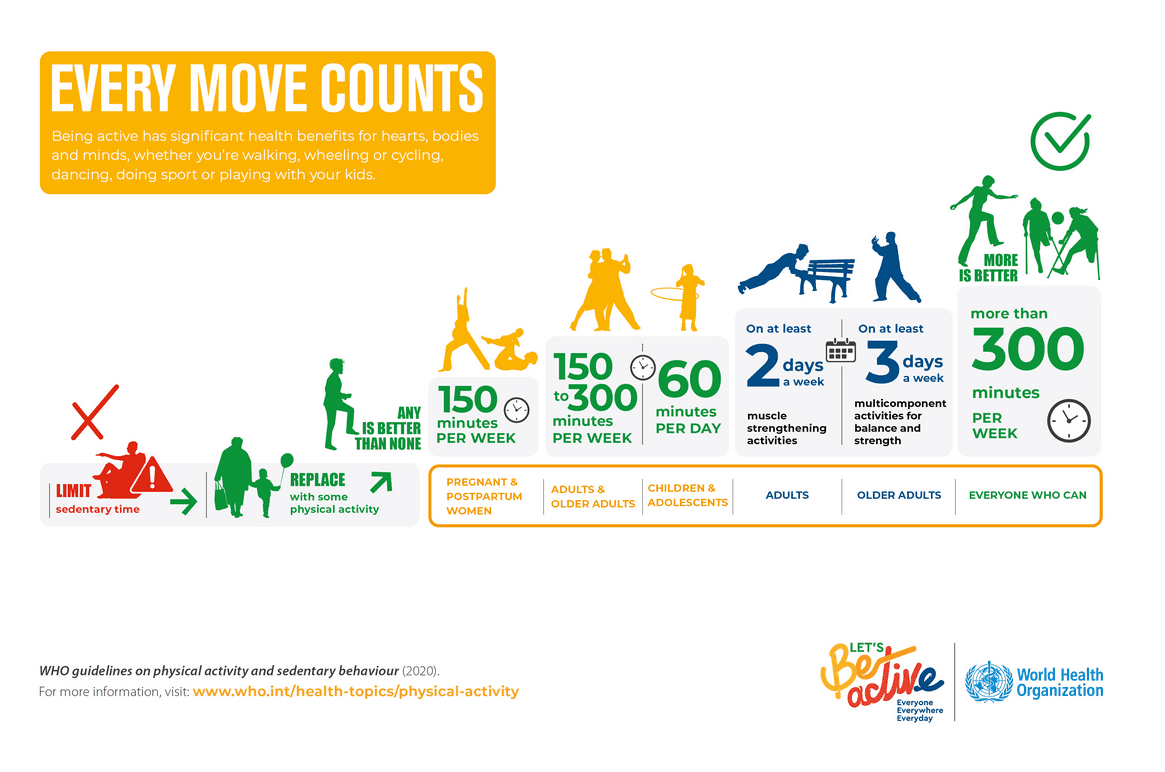

According to the World Health Organization, 31 percent of adults (about 1.8 billion people) and 81 percent of adolescents are insufficiently active. The consequences for the healthcare system and society are staggering. The world faces an epidemic of inactivity, and the cure has been within reach all along.

The Global Burden of Inactivity

In much of the industrialized world, movement has been engineered out of daily life. Cities are built for cars rather than people. Jobs are increasingly screen-based. Children spend more time sitting indoors than exploring outdoors. What was once a natural part of human existence has become optional, and often inconvenient. The result is a worldwide decline in physical activity that has quietly reshaped public health.

Sedentary lifestyles have become a silent epidemic. People who are physically inactive face a 20–30% higher risk of death compared with those who are sufficiently active, according to WHO data. Inactive individuals are also significantly more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and mental health disorders. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), insufficient physical activity is responsible for an estimated US $192 billion in annual healthcare costs in the United States, representing roughly 4% of total national healthcare expenditures. When losses in productivity and premature mortality are included, the overall economic burden is substantially higher. Globally, the cost of physical inactivity runs into hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

This crisis is not confined to any one region or demographic. It cuts across income levels, cultures, and generations. Yet its consequences fall unevenly. Those with access to safe streets, green spaces, and affordable recreational facilities are far more likely to stay active, while marginalized populations face greater barriers to movement. In this sense, the inequality of movement has become a new and urgent determinant of health.

Exercise as a Proven Medical Intervention

Few interventions in modern medicine deliver benefits as broad, reliable, and cost-effective as physical activity. Regular exercise strengthens the heart, improves circulation, regulates blood pressure, and reduces systemic inflammation. It enhances insulin sensitivity, helping to prevent and manage type 2 diabetes, and supports bone density, muscular strength, and balance, thereby reducing falls and fractures among older adults. In many ways, movement is the body’s original form of self-repair.

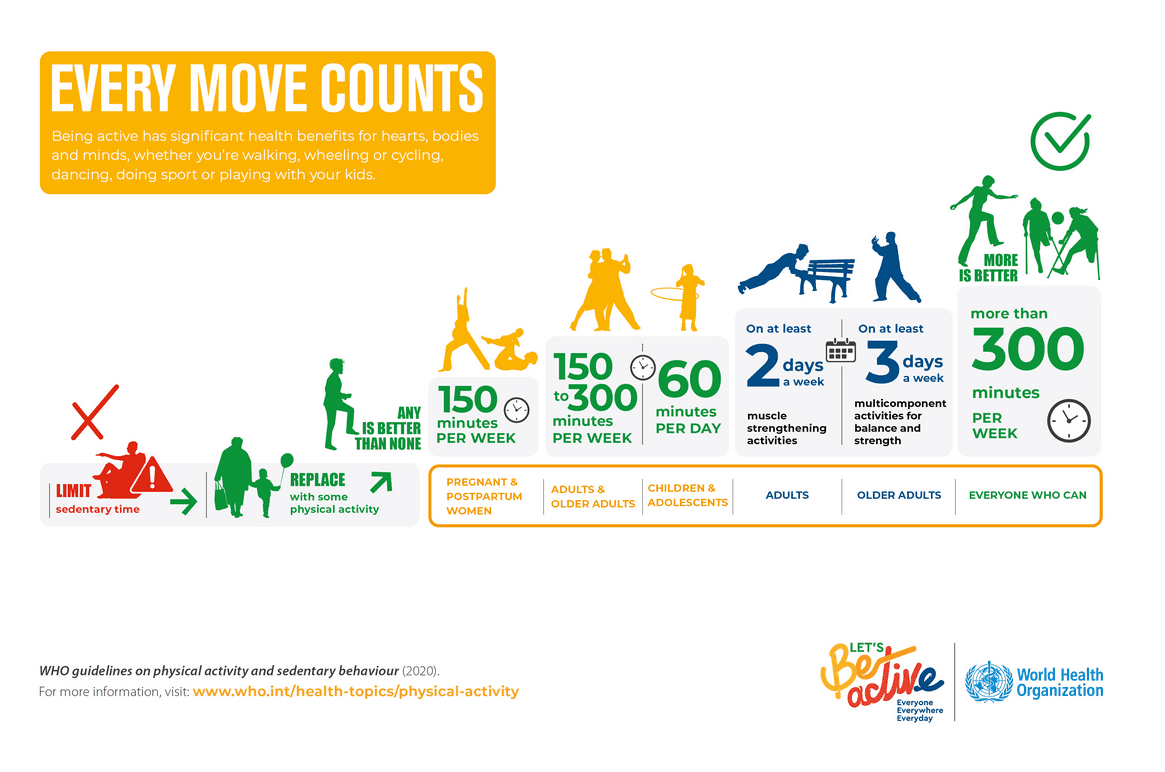

The effects extend far beyond the physical. Exercise stimulates the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins, which elevate mood, sharpen focus, and protect against cognitive decline. According to the World Health Organization, adults should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity each week, equivalent to about 30 minutes of brisk walking on five days. This level of activity is not merely beneficial. It is clinically proven to reduce the risk and severity of depression. A 2022 JAMA Psychiatry meta-analysis involving more than 190,000 participants found that adults who met the recommended activity levels had a 25% lower risk of developing depression compared with those who were inactive. The authors estimated that if all inactive adults achieved the minimum recommended level, 11.5% of global depression cases could be prevented. Similarly, a 2020 BMC Public Health review of randomised controlled trials concluded that physical activity interventions produced a moderate, statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms across age groups.

The concept of “exercise as medicine” is not rhetorical.

Controlled trials published in the British Medical Journal have shown that structured exercise programs equal or outperform pharmacological treatments in improving outcomes for chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and stroke recovery. In cardiac rehabilitation, for example, patients who participated in supervised exercise programs experienced 20 to 30 percent reductions in all-cause mortality, according to meta-analyses reported in Circulation. Similarly, individuals with type 2 diabetes who engaged in combined aerobic and resistance training achieved better glycemic control than those receiving standard care alone.

Hospitals and clinics that integrate movement into their care pathways are seeing tangible improvements. Programs such as Exercise is Medicine, initiated by the American College of Sports Medicine, have helped thousands of physicians incorporate physical activity counselling and referral systems into patient care. Facilities that prescribe and monitor exercise as part of treatment report shorter recovery times, higher patient satisfaction, and reduced readmission rates.

Yes, it is, at its heart, remarkably simple. When the human body moves, every system comes alive. The heart pumps more efficiently, delivering oxygen and nutrients to tissues that renew themselves through use. Muscles contract and release, improving circulation and supporting metabolic balance. The brain releases hormones and neurotransmitters that sharpen focus, lift mood, and protect against cognitive decline. Even the immune system becomes more responsive, better equipped to repair and defend. Physical activity is therefore not an optional behavior but a biological necessity (the condition under which the body was designed to function). A body that moves regularly is far less likely to depend on medication, develop chronic disease, or experience the cascade of health problems linked to inactivity. But the influence of movement extends beyond physiology. People who begin to be active often find their habits changing in parallel: they eat more mindfully, sleep more deeply, and take greater responsibility for their wellbeing. Over time, exercise reshapes identity as much as it reshapes the body. It can replace harmful behaviors (smoking, excessive drinking, constant overconsumption, poor sleep cycles, high sedentary time, and so on) with a sense of control, energy, and purpose. Movement is not merely the product of health; it is its starting point, its driver, and its most enduring expression for lifelong health.

The challenge that remains is not scientific but structural: how to translate what we know into what we do.

Why Healthcare Still Prescribes Pills Instead of Movement

The underuse of exercise as a medical intervention reflects a combination of systemic inertia, educational gaps, and cultural priorities that favor treatment over prevention. In most medical schools, future physicians receive little or no training in exercise science, health behavior change, or motivational counselling. A review published in The Lancet Public Health found that fewer than half of medical curricula worldwide include structured education on physical activity. As a result, many doctors graduate with a strong understanding of pharmacology but minimal knowledge of how to prescribe or support movement as a therapeutic tool.

Within clinical practice, short consultations and outcome-based reimbursement models leave little room for preventive care. Healthcare systems are designed to react to illness, not to sustain wellness. Doctors often acknowledge the importance of physical activity but feel ill-equipped to translate general advice into personalized, safe, and realistic prescriptions. Many also cite a lack of institutional support: few hospitals maintain referral networks that connect patients to qualified exercise professionals or community programs.

The barriers extend well beyond healthcare settings. Modern lifestyles, shaped by urban design, long working hours, and digital dependence, make inactivity the default. For many individuals, even when motivation is present, opportunities for movement are limited by safety concerns, financial constraints, or a lack of accessible facilities. Promoting physical activity therefore requires more than clinical advice; it demands a broader social and environmental framework that enables healthy choices to become the easy, automatic ones.

The Economic and Social Payoff

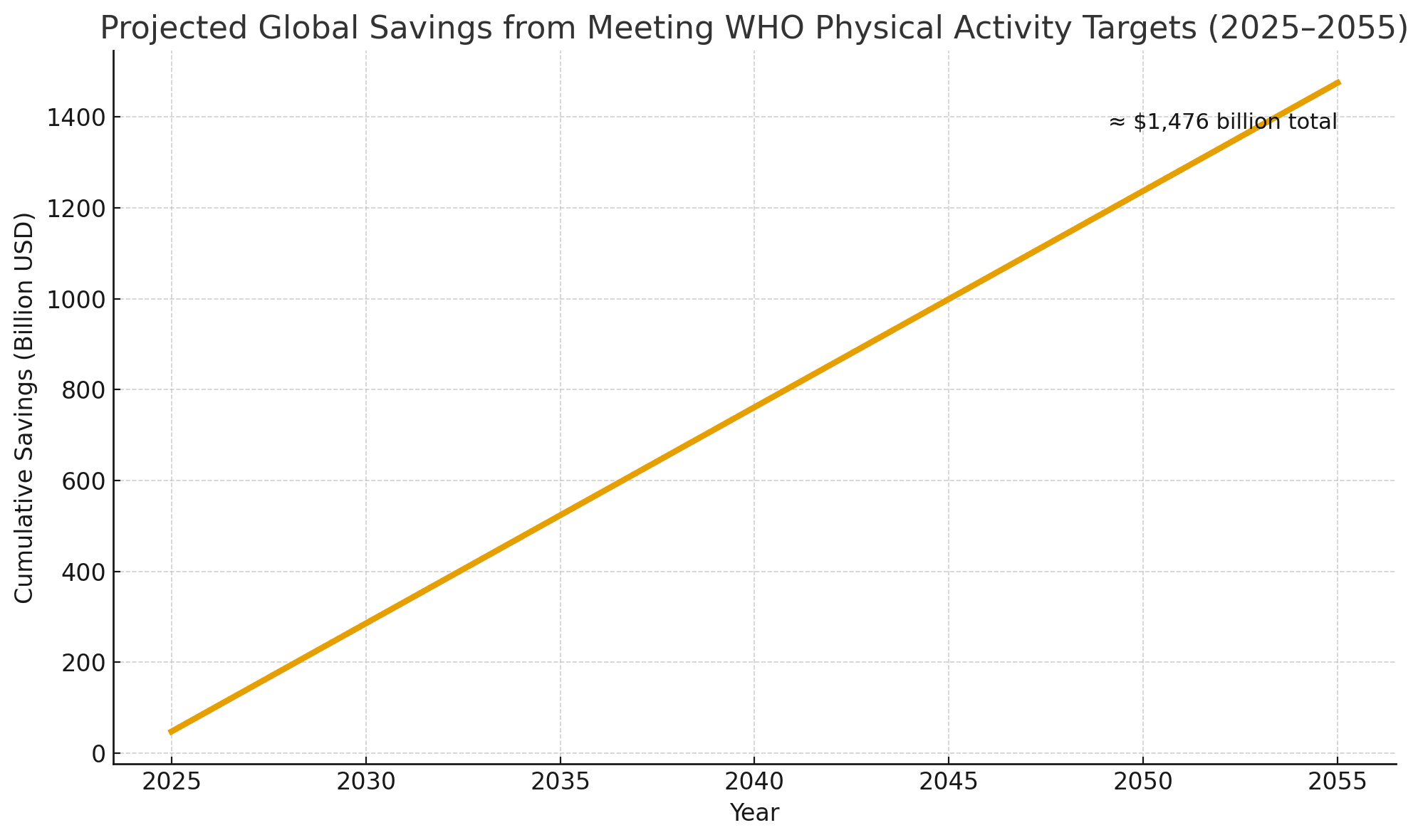

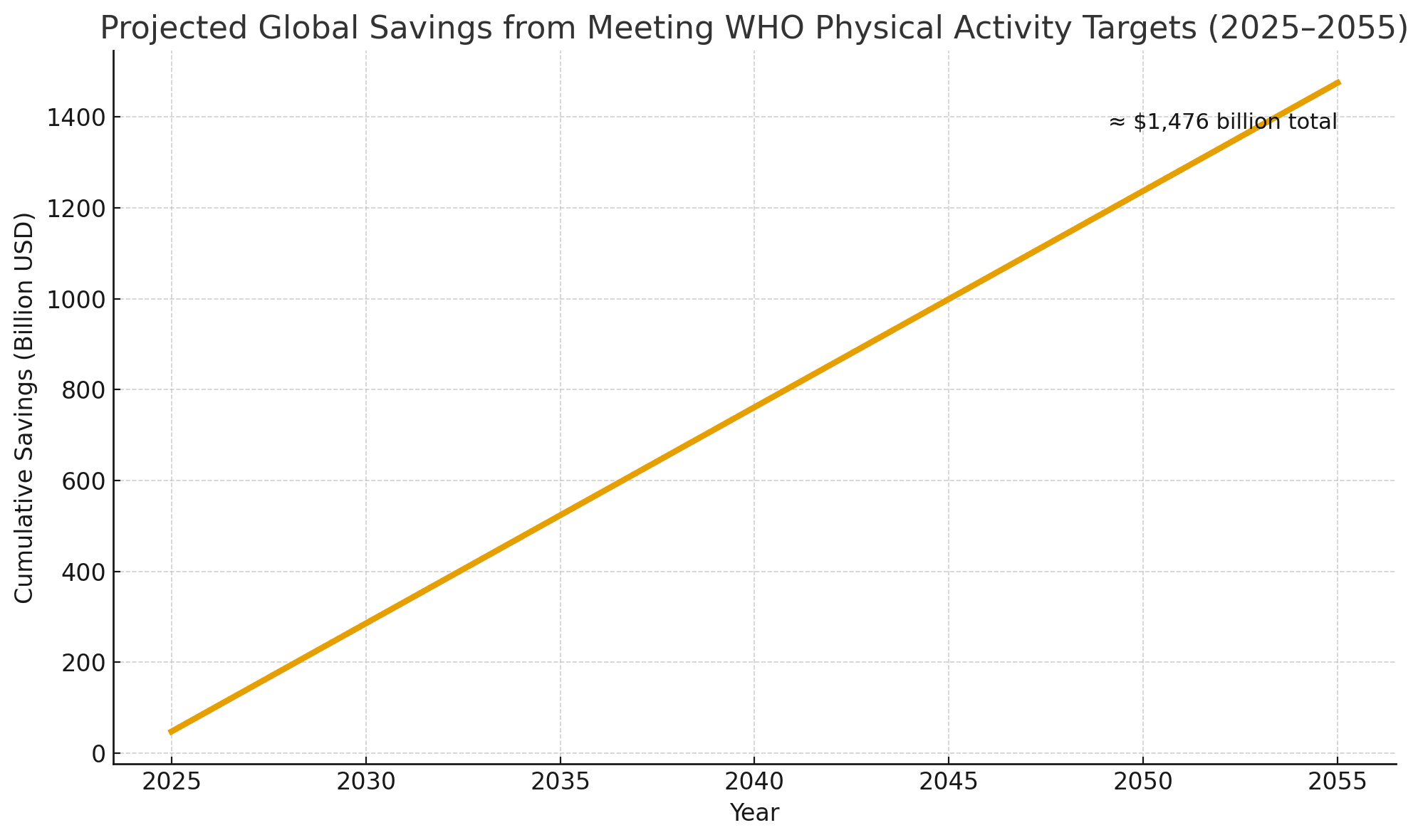

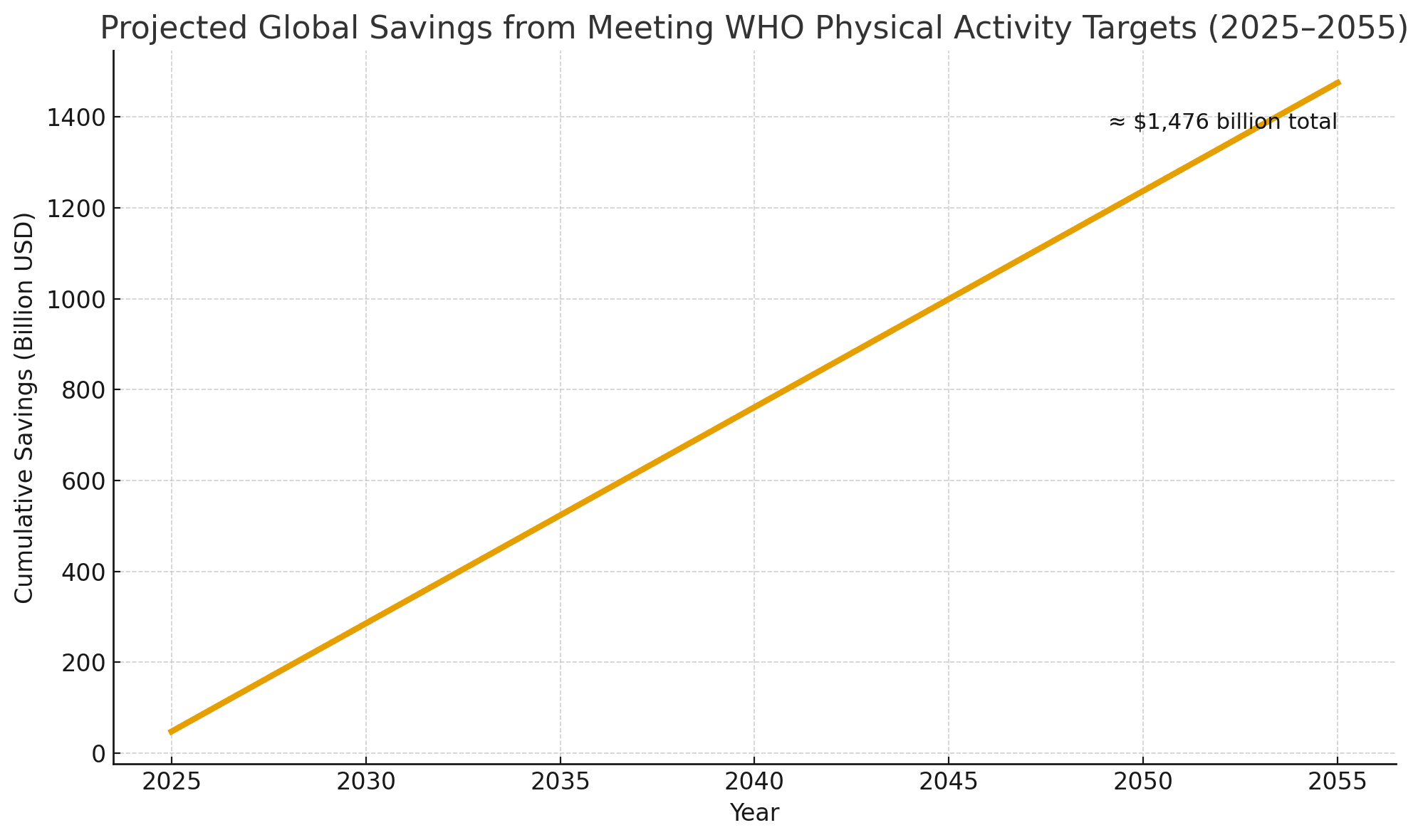

The returns on investing in physical activity extend far beyond individual wellbeing. They strengthen economies, reduce inequality, and build more resilient societies. Preventive care based on movement lowers hospital admissions, reduces medication use, and delays the onset of chronic disease and disability. A 2023 Lancet Global Health analysis estimated that meeting the World Health Organization’s physical activity targets could save US $47.6 billion annually in global healthcare costs and productivity losses.

The benefits are not confined to healthcare budgets. Active populations tend to be more productive, take fewer sick days, and remain in the workforce longer. Communities that promote physical activity also report higher levels of mental wellbeing, lower crime rates, and greater social cohesion. Movement fosters connection. People who walk, cycle, or play together build trust and belonging, both of which are protective factors for public health.

Physical inactivity, by contrast, deepens social and economic divides. Neighborhoods without safe walking routes or affordable facilities experience higher rates of chronic illness and lower life expectancy. Addressing these inequities is therefore not only a moral imperative but also an economic strategy: every dollar invested in active infrastructure, community sport, or physical education yields multiple dollars in healthcare savings and productivity gains.

© 2025 qp360. This visual is freely available for public use under an open-access license.

Prescribing Movement: Emerging Global Models

Transforming the science of physical activity into daily medical practice requires more than awareness; it requires systems. Several models illustrate how exercise can be systematically prescribed within healthcare frameworks. In Finland, physicians issue individualized “exercise prescriptions” that connect patients to local activity resources. The UK’s Moving Medicine program provides clinicians with evidence-based conversation guides for integrating physical activity into patient care. Singapore’s National Steps Challenge combines wearable technology with public incentives, leading to a 20% increase in average daily step counts across participants.

These programs share a common principle: exercise must be prescribed, monitored, and supported like any other medical treatment. Patients need guidance on how much activity to do, how to progress safely, and how to sustain motivation. When healthcare providers treat movement as a serious intervention rather than lifestyle advice, participation rises and outcomes improve.

Technology as a Tool for Change

Digital innovation has revolutionized how health professionals promote movement. Wearable devices, smartphone apps, and remote monitoring platforms now allow clinicians to track physical activity, analyze patterns, and personalize exercise recommendations in real time. When used effectively, these tools enhance accountability, increase adherence, and empower individuals to take ownership of their health.

However, technology alone cannot sustain lasting behavioral change. Fitness apps and online workouts can provide an initial boost of motivation, but the effect often fades without social support or environmental reinforcement. Research consistently shows that digital interventions are most successful when combined with human connection and community engagement.

A 2023 review published in Frontiers in Psychology found that digital programs incorporating social features, such as peer interaction, group challenges, or community coaching, achieved significantly greater increases in physical activity than technology-only approaches. Similarly, a 2024 JMIR Aging study demonstrated that older adults who used a peer-supported physical activity app improved their daily step counts and functional fitness far more than those using the app alone.

Technology can track the steps, but people and communities inspire the journey.

Building a Movement-Based Healthcare System

Education: Medical schools should treat exercise physiology and behavioral counselling as core elements of clinical training, ensuring that future physicians can prescribe and guide physical activity with confidence. Education, however, must begin much earlier. Schools should prioritize high-quality physical education that fosters not only fitness but also lifelong enjoyment of movement, body awareness, and health literacy. Beyond classrooms, public education campaigns can help people understand that physical activity is not an optional hobby but a daily necessity, as fundamental to wellbeing as sleep, nutrition, or social connection. Building this culture of understanding from childhood through adulthood is essential if movement is to become a universal habit rather than a medical afterthought.

Policy: Health systems must begin to reward prevention. Insurance providers should recognize and cover structured exercise interventions, rehabilitation through movement, and community-based fitness programs as legitimate, evidence-based treatments. Governments should integrate physical activity goals into national health strategies, monitor population movement levels, and include physical activity metrics in public health reporting. Policies that incentivize walking, cycling, and active commuting, for example through tax benefits or employer wellness programs, can make healthy behavior the default choice rather than the difficult one.

Infrastructure: Cities must prioritize walkability, cycling networks, and accessible recreational spaces as essential public health investments, not optional amenities. Urban planning that encourages active transport, outdoor recreation, and equitable access to green space can dramatically improve both physical and mental health outcomes. Safe, well-lit streets, interconnected paths, and public transport systems that favor active travel empower entire populations to move more naturally. By designing communities around movement, societies can create environments that sustain wellbeing.

Culture: Society must redefine exercise. It should no longer be viewed as a pastime for the motivated few but as a universal determinant of health, relevant to every stage of life and every community. Media, workplaces, and educational institutions all play a role in normalizing movement, celebrating it not only as fitness but as joy, connection, and resilience. When cultures value movement as deeply as they value medicine, health becomes not just a policy goal but a shared way of living.

Rediscovering the Oldest Medicine

The most powerful form of medicine has existed since the dawn of humanity. It requires no prescription pad, no dosage chart, and no pharmaceutical patent. Yet its potential remains vastly underused.

Physical activity can prevent disease, restore health, and extend life expectancy. It is both individual and collective, personal and political. To harness its full potential, the world must move beyond rhetoric and embed exercise into every level of healthcare and public policy.

A future where doctors prescribe movement, where cities are built for walking, and where activity is seen as a human right rather than a privilege is within reach. The question is not whether exercise works, but whether we can reshape how we value it. When activity is woven into the systems that shape our choices, health stops being reactive and becomes a shared cultural habit.

If physical activity could be packaged in a pill, it would be the single most widely prescribed and beneficial medicine in the nation.

~ Dr Robert Butler (founding director of the U.S. National Institute on Aging)

Sources

• World Health Organization (2022): Physical activity – A global public health problem

• British Heart Foundation (2017): Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Report

• American Journal of Health Promotion (2025): Inadequate Aerobic Physical Activity and Healthcare Expenditures in the United States: An Updated Cost Estimate

• The Lancet Global Health (2023): The cost of inaction on physical inactivity to public health-care systems: a population-attributable fraction analysis

• World Health Organization (2020). Physical Activity: Be Active Campaign. WHO

• Pearce, M. et al. (2022). “Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Meta-Analysis.” JAMA Psychiatry. PubMed

• Morres, I. et al. (2020). “Physical Activity and Depression: Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health

• British Medical Journal (2013): Naci, H. & Ioannidis, J.P.A. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes

• Circulation (2016): Anderson, L. et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease

• American College of Sports Medicine: Exercise is Medicine Initiative

• Government of Finland (2019): Physical Activity Prescription Programme

• Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine (UK): Moving Medicine – Physical Activity in Clinical Practice

• Health Promotion Board (Singapore, 2023): National Steps Challenge – Annual Report

• Frontiers in Psychology (2023): A Meta-analysis of the Relationship Between Social Support and Physical Activity

• JMIR Aging (2024): Digital Peer-Supported App Intervention to Promote Physical Activity Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

• Dr. Robert N. Butler: Founding Director, U.S. National Institute on Aging – quoted widely in public health literature

Stay Inspired

Get fresh design insights, articles, and resources delivered straight to your inbox.

Latest Insights

Stay Inspired

Get fresh design insights, articles, and resources delivered straight to your inbox.

Research

Oct 20, 2025

Exercise as Medicine: Rethinking Healthcare Through Movement

Exercise as Medicine: Rethinking Healthcare Through Movement

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

Introduction

Across the world, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular illness, diabetes, cancer, and depression are rising faster than healthcare systems can contain them. Yet one of the most powerful, low-cost, and universally accessible treatments remains underused: movement itself. Regular physical activity prevents, manages, and reverses many of the conditions that shorten lives and strain economies. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, it is still prescribed far less often than pills or procedures. According to the British Heart Foundation, insufficient physical activity contributes to more than five million preventable deaths each year.

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

The Missing Prescription

Across the world’s clinics and hospitals, patients wait in search of relief from fatigue, pain, and the slow erosion of wellbeing that chronic illness brings. They leave with prescriptions for pills or procedures, but almost never with one for movement. This absence is more than an oversight; it’s a paradox at the heart of modern healthcare.

Physical inactivity now rivals smoking and poor diet as one of the leading causes of premature death, claiming millions of lives each year despite being entirely preventable. The idea that movement itself could serve as medicine remains peripheral in clinical practice, even as the evidence grows impossible to ignore.

Regular physical activity strengthens nearly every system of the human body. It improves cardiovascular function, enhances immune response, balances metabolism, sharpens cognition, and elevates mood. Exercise is both prevention and cure, capable of reducing the risk of more than 30 chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, several cancers, and dementia. Yet health systems continue to invest primarily in treating illness rather than cultivating health.

According to the World Health Organization, 31 percent of adults (about 1.8 billion people) and 81 percent of adolescents are insufficiently active. The consequences for the healthcare system and society are staggering. The world faces an epidemic of inactivity, and the cure has been within reach all along.

The Global Burden of Inactivity

In much of the industrialized world, movement has been engineered out of daily life. Cities are built for cars rather than people. Jobs are increasingly screen-based. Children spend more time sitting indoors than exploring outdoors. What was once a natural part of human existence has become optional, and often inconvenient. The result is a worldwide decline in physical activity that has quietly reshaped public health.

Sedentary lifestyles have become a silent epidemic. People who are physically inactive face a 20–30% higher risk of death compared with those who are sufficiently active, according to WHO data. Inactive individuals are also significantly more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and mental health disorders. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), insufficient physical activity is responsible for an estimated US $192 billion in annual healthcare costs in the United States, representing roughly 4% of total national healthcare expenditures. When losses in productivity and premature mortality are included, the overall economic burden is substantially higher. Globally, the cost of physical inactivity runs into hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

This crisis is not confined to any one region or demographic. It cuts across income levels, cultures, and generations. Yet its consequences fall unevenly. Those with access to safe streets, green spaces, and affordable recreational facilities are far more likely to stay active, while marginalized populations face greater barriers to movement. In this sense, the inequality of movement has become a new and urgent determinant of health.

Exercise as a Proven Medical Intervention

Few interventions in modern medicine deliver benefits as broad, reliable, and cost-effective as physical activity. Regular exercise strengthens the heart, improves circulation, regulates blood pressure, and reduces systemic inflammation. It enhances insulin sensitivity, helping to prevent and manage type 2 diabetes, and supports bone density, muscular strength, and balance, thereby reducing falls and fractures among older adults. In many ways, movement is the body’s original form of self-repair.

The effects extend far beyond the physical. Exercise stimulates the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins, which elevate mood, sharpen focus, and protect against cognitive decline. According to the World Health Organization, adults should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity each week, equivalent to about 30 minutes of brisk walking on five days. This level of activity is not merely beneficial. It is clinically proven to reduce the risk and severity of depression. A 2022 JAMA Psychiatry meta-analysis involving more than 190,000 participants found that adults who met the recommended activity levels had a 25% lower risk of developing depression compared with those who were inactive. The authors estimated that if all inactive adults achieved the minimum recommended level, 11.5% of global depression cases could be prevented. Similarly, a 2020 BMC Public Health review of randomised controlled trials concluded that physical activity interventions produced a moderate, statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms across age groups.

The concept of “exercise as medicine” is not rhetorical.

Controlled trials published in the British Medical Journal have shown that structured exercise programs equal or outperform pharmacological treatments in improving outcomes for chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and stroke recovery. In cardiac rehabilitation, for example, patients who participated in supervised exercise programs experienced 20 to 30 percent reductions in all-cause mortality, according to meta-analyses reported in Circulation. Similarly, individuals with type 2 diabetes who engaged in combined aerobic and resistance training achieved better glycemic control than those receiving standard care alone.

Hospitals and clinics that integrate movement into their care pathways are seeing tangible improvements. Programs such as Exercise is Medicine, initiated by the American College of Sports Medicine, have helped thousands of physicians incorporate physical activity counselling and referral systems into patient care. Facilities that prescribe and monitor exercise as part of treatment report shorter recovery times, higher patient satisfaction, and reduced readmission rates.

Yes, it is, at its heart, remarkably simple. When the human body moves, every system comes alive. The heart pumps more efficiently, delivering oxygen and nutrients to tissues that renew themselves through use. Muscles contract and release, improving circulation and supporting metabolic balance. The brain releases hormones and neurotransmitters that sharpen focus, lift mood, and protect against cognitive decline. Even the immune system becomes more responsive, better equipped to repair and defend. Physical activity is therefore not an optional behavior but a biological necessity (the condition under which the body was designed to function). A body that moves regularly is far less likely to depend on medication, develop chronic disease, or experience the cascade of health problems linked to inactivity. But the influence of movement extends beyond physiology. People who begin to be active often find their habits changing in parallel: they eat more mindfully, sleep more deeply, and take greater responsibility for their wellbeing. Over time, exercise reshapes identity as much as it reshapes the body. It can replace harmful behaviors (smoking, excessive drinking, constant overconsumption, poor sleep cycles, high sedentary time, and so on) with a sense of control, energy, and purpose. Movement is not merely the product of health; it is its starting point, its driver, and its most enduring expression for lifelong health.

The challenge that remains is not scientific but structural: how to translate what we know into what we do.

Why Healthcare Still Prescribes Pills Instead of Movement

The underuse of exercise as a medical intervention reflects a combination of systemic inertia, educational gaps, and cultural priorities that favor treatment over prevention. In most medical schools, future physicians receive little or no training in exercise science, health behavior change, or motivational counselling. A review published in The Lancet Public Health found that fewer than half of medical curricula worldwide include structured education on physical activity. As a result, many doctors graduate with a strong understanding of pharmacology but minimal knowledge of how to prescribe or support movement as a therapeutic tool.

Within clinical practice, short consultations and outcome-based reimbursement models leave little room for preventive care. Healthcare systems are designed to react to illness, not to sustain wellness. Doctors often acknowledge the importance of physical activity but feel ill-equipped to translate general advice into personalized, safe, and realistic prescriptions. Many also cite a lack of institutional support: few hospitals maintain referral networks that connect patients to qualified exercise professionals or community programs.

The barriers extend well beyond healthcare settings. Modern lifestyles, shaped by urban design, long working hours, and digital dependence, make inactivity the default. For many individuals, even when motivation is present, opportunities for movement are limited by safety concerns, financial constraints, or a lack of accessible facilities. Promoting physical activity therefore requires more than clinical advice; it demands a broader social and environmental framework that enables healthy choices to become the easy, automatic ones.

The Economic and Social Payoff

The returns on investing in physical activity extend far beyond individual wellbeing. They strengthen economies, reduce inequality, and build more resilient societies. Preventive care based on movement lowers hospital admissions, reduces medication use, and delays the onset of chronic disease and disability. A 2023 Lancet Global Health analysis estimated that meeting the World Health Organization’s physical activity targets could save US $47.6 billion annually in global healthcare costs and productivity losses.

The benefits are not confined to healthcare budgets. Active populations tend to be more productive, take fewer sick days, and remain in the workforce longer. Communities that promote physical activity also report higher levels of mental wellbeing, lower crime rates, and greater social cohesion. Movement fosters connection. People who walk, cycle, or play together build trust and belonging, both of which are protective factors for public health.

Physical inactivity, by contrast, deepens social and economic divides. Neighborhoods without safe walking routes or affordable facilities experience higher rates of chronic illness and lower life expectancy. Addressing these inequities is therefore not only a moral imperative but also an economic strategy: every dollar invested in active infrastructure, community sport, or physical education yields multiple dollars in healthcare savings and productivity gains.

© 2025 qp360. This visual is freely available for public use under an open-access license.

Prescribing Movement: Emerging Global Models

Transforming the science of physical activity into daily medical practice requires more than awareness; it requires systems. Several models illustrate how exercise can be systematically prescribed within healthcare frameworks. In Finland, physicians issue individualized “exercise prescriptions” that connect patients to local activity resources. The UK’s Moving Medicine program provides clinicians with evidence-based conversation guides for integrating physical activity into patient care. Singapore’s National Steps Challenge combines wearable technology with public incentives, leading to a 20% increase in average daily step counts across participants.

These programs share a common principle: exercise must be prescribed, monitored, and supported like any other medical treatment. Patients need guidance on how much activity to do, how to progress safely, and how to sustain motivation. When healthcare providers treat movement as a serious intervention rather than lifestyle advice, participation rises and outcomes improve.

Technology as a Tool for Change

Digital innovation has revolutionized how health professionals promote movement. Wearable devices, smartphone apps, and remote monitoring platforms now allow clinicians to track physical activity, analyze patterns, and personalize exercise recommendations in real time. When used effectively, these tools enhance accountability, increase adherence, and empower individuals to take ownership of their health.

However, technology alone cannot sustain lasting behavioral change. Fitness apps and online workouts can provide an initial boost of motivation, but the effect often fades without social support or environmental reinforcement. Research consistently shows that digital interventions are most successful when combined with human connection and community engagement.

A 2023 review published in Frontiers in Psychology found that digital programs incorporating social features, such as peer interaction, group challenges, or community coaching, achieved significantly greater increases in physical activity than technology-only approaches. Similarly, a 2024 JMIR Aging study demonstrated that older adults who used a peer-supported physical activity app improved their daily step counts and functional fitness far more than those using the app alone.

Technology can track the steps, but people and communities inspire the journey.

Building a Movement-Based Healthcare System

Education: Medical schools should treat exercise physiology and behavioral counselling as core elements of clinical training, ensuring that future physicians can prescribe and guide physical activity with confidence. Education, however, must begin much earlier. Schools should prioritize high-quality physical education that fosters not only fitness but also lifelong enjoyment of movement, body awareness, and health literacy. Beyond classrooms, public education campaigns can help people understand that physical activity is not an optional hobby but a daily necessity, as fundamental to wellbeing as sleep, nutrition, or social connection. Building this culture of understanding from childhood through adulthood is essential if movement is to become a universal habit rather than a medical afterthought.

Policy: Health systems must begin to reward prevention. Insurance providers should recognize and cover structured exercise interventions, rehabilitation through movement, and community-based fitness programs as legitimate, evidence-based treatments. Governments should integrate physical activity goals into national health strategies, monitor population movement levels, and include physical activity metrics in public health reporting. Policies that incentivize walking, cycling, and active commuting, for example through tax benefits or employer wellness programs, can make healthy behavior the default choice rather than the difficult one.

Infrastructure: Cities must prioritize walkability, cycling networks, and accessible recreational spaces as essential public health investments, not optional amenities. Urban planning that encourages active transport, outdoor recreation, and equitable access to green space can dramatically improve both physical and mental health outcomes. Safe, well-lit streets, interconnected paths, and public transport systems that favor active travel empower entire populations to move more naturally. By designing communities around movement, societies can create environments that sustain wellbeing.

Culture: Society must redefine exercise. It should no longer be viewed as a pastime for the motivated few but as a universal determinant of health, relevant to every stage of life and every community. Media, workplaces, and educational institutions all play a role in normalizing movement, celebrating it not only as fitness but as joy, connection, and resilience. When cultures value movement as deeply as they value medicine, health becomes not just a policy goal but a shared way of living.

Rediscovering the Oldest Medicine

The most powerful form of medicine has existed since the dawn of humanity. It requires no prescription pad, no dosage chart, and no pharmaceutical patent. Yet its potential remains vastly underused.

Physical activity can prevent disease, restore health, and extend life expectancy. It is both individual and collective, personal and political. To harness its full potential, the world must move beyond rhetoric and embed exercise into every level of healthcare and public policy.

A future where doctors prescribe movement, where cities are built for walking, and where activity is seen as a human right rather than a privilege is within reach. The question is not whether exercise works, but whether we can reshape how we value it. When activity is woven into the systems that shape our choices, health stops being reactive and becomes a shared cultural habit.

If physical activity could be packaged in a pill, it would be the single most widely prescribed and beneficial medicine in the nation.

~ Dr Robert Butler (founding director of the U.S. National Institute on Aging)

Sources

• World Health Organization (2022): Physical activity – A global public health problem

• British Heart Foundation (2017): Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Report

• American Journal of Health Promotion (2025): Inadequate Aerobic Physical Activity and Healthcare Expenditures in the United States: An Updated Cost Estimate

• The Lancet Global Health (2023): The cost of inaction on physical inactivity to public health-care systems: a population-attributable fraction analysis

• World Health Organization (2020). Physical Activity: Be Active Campaign. WHO

• Pearce, M. et al. (2022). “Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Meta-Analysis.” JAMA Psychiatry. PubMed

• Morres, I. et al. (2020). “Physical Activity and Depression: Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health

• British Medical Journal (2013): Naci, H. & Ioannidis, J.P.A. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes

• Circulation (2016): Anderson, L. et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease

• American College of Sports Medicine: Exercise is Medicine Initiative

• Government of Finland (2019): Physical Activity Prescription Programme

• Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine (UK): Moving Medicine – Physical Activity in Clinical Practice

• Health Promotion Board (Singapore, 2023): National Steps Challenge – Annual Report

• Frontiers in Psychology (2023): A Meta-analysis of the Relationship Between Social Support and Physical Activity

• JMIR Aging (2024): Digital Peer-Supported App Intervention to Promote Physical Activity Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

• Dr. Robert N. Butler: Founding Director, U.S. National Institute on Aging – quoted widely in public health literature

Stay Inspired

Get fresh design insights, articles, and resources delivered straight to your inbox.

Latest Insights

Stay Inspired

Get fresh design insights, articles, and resources delivered straight to your inbox.

Research

Oct 20, 2025

Exercise as Medicine: Rethinking Healthcare Through Movement

Exercise as Medicine: Rethinking Healthcare Through Movement

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

Introduction

Across the world, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular illness, diabetes, cancer, and depression are rising faster than healthcare systems can contain them. Yet one of the most powerful, low-cost, and universally accessible treatments remains underused: movement itself. Regular physical activity prevents, manages, and reverses many of the conditions that shorten lives and strain economies. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, it is still prescribed far less often than pills or procedures. According to the British Heart Foundation, insufficient physical activity contributes to more than five million preventable deaths each year.

This article explores the scientific foundation of exercise as medicine and the systemic reasons it remains neglected. It examines how reimagining physical activity as a clinical and cultural priority could transform not only individual health but also the sustainability of healthcare systems and the wellbeing of entire societies.

The Missing Prescription

Across the world’s clinics and hospitals, patients wait in search of relief from fatigue, pain, and the slow erosion of wellbeing that chronic illness brings. They leave with prescriptions for pills or procedures, but almost never with one for movement. This absence is more than an oversight; it’s a paradox at the heart of modern healthcare.

Physical inactivity now rivals smoking and poor diet as one of the leading causes of premature death, claiming millions of lives each year despite being entirely preventable. The idea that movement itself could serve as medicine remains peripheral in clinical practice, even as the evidence grows impossible to ignore.

Regular physical activity strengthens nearly every system of the human body. It improves cardiovascular function, enhances immune response, balances metabolism, sharpens cognition, and elevates mood. Exercise is both prevention and cure, capable of reducing the risk of more than 30 chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, several cancers, and dementia. Yet health systems continue to invest primarily in treating illness rather than cultivating health.

According to the World Health Organization, 31 percent of adults (about 1.8 billion people) and 81 percent of adolescents are insufficiently active. The consequences for the healthcare system and society are staggering. The world faces an epidemic of inactivity, and the cure has been within reach all along.

The Global Burden of Inactivity

In much of the industrialized world, movement has been engineered out of daily life. Cities are built for cars rather than people. Jobs are increasingly screen-based. Children spend more time sitting indoors than exploring outdoors. What was once a natural part of human existence has become optional, and often inconvenient. The result is a worldwide decline in physical activity that has quietly reshaped public health.

Sedentary lifestyles have become a silent epidemic. People who are physically inactive face a 20–30% higher risk of death compared with those who are sufficiently active, according to WHO data. Inactive individuals are also significantly more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and mental health disorders. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), insufficient physical activity is responsible for an estimated US $192 billion in annual healthcare costs in the United States, representing roughly 4% of total national healthcare expenditures. When losses in productivity and premature mortality are included, the overall economic burden is substantially higher. Globally, the cost of physical inactivity runs into hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

This crisis is not confined to any one region or demographic. It cuts across income levels, cultures, and generations. Yet its consequences fall unevenly. Those with access to safe streets, green spaces, and affordable recreational facilities are far more likely to stay active, while marginalized populations face greater barriers to movement. In this sense, the inequality of movement has become a new and urgent determinant of health.

Exercise as a Proven Medical Intervention

Few interventions in modern medicine deliver benefits as broad, reliable, and cost-effective as physical activity. Regular exercise strengthens the heart, improves circulation, regulates blood pressure, and reduces systemic inflammation. It enhances insulin sensitivity, helping to prevent and manage type 2 diabetes, and supports bone density, muscular strength, and balance, thereby reducing falls and fractures among older adults. In many ways, movement is the body’s original form of self-repair.

The effects extend far beyond the physical. Exercise stimulates the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins, which elevate mood, sharpen focus, and protect against cognitive decline. According to the World Health Organization, adults should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity each week, equivalent to about 30 minutes of brisk walking on five days. This level of activity is not merely beneficial. It is clinically proven to reduce the risk and severity of depression. A 2022 JAMA Psychiatry meta-analysis involving more than 190,000 participants found that adults who met the recommended activity levels had a 25% lower risk of developing depression compared with those who were inactive. The authors estimated that if all inactive adults achieved the minimum recommended level, 11.5% of global depression cases could be prevented. Similarly, a 2020 BMC Public Health review of randomised controlled trials concluded that physical activity interventions produced a moderate, statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms across age groups.

The concept of “exercise as medicine” is not rhetorical.

Controlled trials published in the British Medical Journal have shown that structured exercise programs equal or outperform pharmacological treatments in improving outcomes for chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and stroke recovery. In cardiac rehabilitation, for example, patients who participated in supervised exercise programs experienced 20 to 30 percent reductions in all-cause mortality, according to meta-analyses reported in Circulation. Similarly, individuals with type 2 diabetes who engaged in combined aerobic and resistance training achieved better glycemic control than those receiving standard care alone.

Hospitals and clinics that integrate movement into their care pathways are seeing tangible improvements. Programs such as Exercise is Medicine, initiated by the American College of Sports Medicine, have helped thousands of physicians incorporate physical activity counselling and referral systems into patient care. Facilities that prescribe and monitor exercise as part of treatment report shorter recovery times, higher patient satisfaction, and reduced readmission rates.

Yes, it is, at its heart, remarkably simple. When the human body moves, every system comes alive. The heart pumps more efficiently, delivering oxygen and nutrients to tissues that renew themselves through use. Muscles contract and release, improving circulation and supporting metabolic balance. The brain releases hormones and neurotransmitters that sharpen focus, lift mood, and protect against cognitive decline. Even the immune system becomes more responsive, better equipped to repair and defend. Physical activity is therefore not an optional behavior but a biological necessity (the condition under which the body was designed to function). A body that moves regularly is far less likely to depend on medication, develop chronic disease, or experience the cascade of health problems linked to inactivity. But the influence of movement extends beyond physiology. People who begin to be active often find their habits changing in parallel: they eat more mindfully, sleep more deeply, and take greater responsibility for their wellbeing. Over time, exercise reshapes identity as much as it reshapes the body. It can replace harmful behaviors (smoking, excessive drinking, constant overconsumption, poor sleep cycles, high sedentary time, and so on) with a sense of control, energy, and purpose. Movement is not merely the product of health; it is its starting point, its driver, and its most enduring expression for lifelong health.

The challenge that remains is not scientific but structural: how to translate what we know into what we do.

Why Healthcare Still Prescribes Pills Instead of Movement

The underuse of exercise as a medical intervention reflects a combination of systemic inertia, educational gaps, and cultural priorities that favor treatment over prevention. In most medical schools, future physicians receive little or no training in exercise science, health behavior change, or motivational counselling. A review published in The Lancet Public Health found that fewer than half of medical curricula worldwide include structured education on physical activity. As a result, many doctors graduate with a strong understanding of pharmacology but minimal knowledge of how to prescribe or support movement as a therapeutic tool.

Within clinical practice, short consultations and outcome-based reimbursement models leave little room for preventive care. Healthcare systems are designed to react to illness, not to sustain wellness. Doctors often acknowledge the importance of physical activity but feel ill-equipped to translate general advice into personalized, safe, and realistic prescriptions. Many also cite a lack of institutional support: few hospitals maintain referral networks that connect patients to qualified exercise professionals or community programs.

The barriers extend well beyond healthcare settings. Modern lifestyles, shaped by urban design, long working hours, and digital dependence, make inactivity the default. For many individuals, even when motivation is present, opportunities for movement are limited by safety concerns, financial constraints, or a lack of accessible facilities. Promoting physical activity therefore requires more than clinical advice; it demands a broader social and environmental framework that enables healthy choices to become the easy, automatic ones.

The Economic and Social Payoff

The returns on investing in physical activity extend far beyond individual wellbeing. They strengthen economies, reduce inequality, and build more resilient societies. Preventive care based on movement lowers hospital admissions, reduces medication use, and delays the onset of chronic disease and disability. A 2023 Lancet Global Health analysis estimated that meeting the World Health Organization’s physical activity targets could save US $47.6 billion annually in global healthcare costs and productivity losses.

The benefits are not confined to healthcare budgets. Active populations tend to be more productive, take fewer sick days, and remain in the workforce longer. Communities that promote physical activity also report higher levels of mental wellbeing, lower crime rates, and greater social cohesion. Movement fosters connection. People who walk, cycle, or play together build trust and belonging, both of which are protective factors for public health.

Physical inactivity, by contrast, deepens social and economic divides. Neighborhoods without safe walking routes or affordable facilities experience higher rates of chronic illness and lower life expectancy. Addressing these inequities is therefore not only a moral imperative but also an economic strategy: every dollar invested in active infrastructure, community sport, or physical education yields multiple dollars in healthcare savings and productivity gains.

© 2025 qp360. This visual is freely available for public use under an open-access license.

Prescribing Movement: Emerging Global Models

Transforming the science of physical activity into daily medical practice requires more than awareness; it requires systems. Several models illustrate how exercise can be systematically prescribed within healthcare frameworks. In Finland, physicians issue individualized “exercise prescriptions” that connect patients to local activity resources. The UK’s Moving Medicine program provides clinicians with evidence-based conversation guides for integrating physical activity into patient care. Singapore’s National Steps Challenge combines wearable technology with public incentives, leading to a 20% increase in average daily step counts across participants.

These programs share a common principle: exercise must be prescribed, monitored, and supported like any other medical treatment. Patients need guidance on how much activity to do, how to progress safely, and how to sustain motivation. When healthcare providers treat movement as a serious intervention rather than lifestyle advice, participation rises and outcomes improve.

Technology as a Tool for Change

Digital innovation has revolutionized how health professionals promote movement. Wearable devices, smartphone apps, and remote monitoring platforms now allow clinicians to track physical activity, analyze patterns, and personalize exercise recommendations in real time. When used effectively, these tools enhance accountability, increase adherence, and empower individuals to take ownership of their health.

However, technology alone cannot sustain lasting behavioral change. Fitness apps and online workouts can provide an initial boost of motivation, but the effect often fades without social support or environmental reinforcement. Research consistently shows that digital interventions are most successful when combined with human connection and community engagement.

A 2023 review published in Frontiers in Psychology found that digital programs incorporating social features, such as peer interaction, group challenges, or community coaching, achieved significantly greater increases in physical activity than technology-only approaches. Similarly, a 2024 JMIR Aging study demonstrated that older adults who used a peer-supported physical activity app improved their daily step counts and functional fitness far more than those using the app alone.

Technology can track the steps, but people and communities inspire the journey.

Building a Movement-Based Healthcare System

Education: Medical schools should treat exercise physiology and behavioral counselling as core elements of clinical training, ensuring that future physicians can prescribe and guide physical activity with confidence. Education, however, must begin much earlier. Schools should prioritize high-quality physical education that fosters not only fitness but also lifelong enjoyment of movement, body awareness, and health literacy. Beyond classrooms, public education campaigns can help people understand that physical activity is not an optional hobby but a daily necessity, as fundamental to wellbeing as sleep, nutrition, or social connection. Building this culture of understanding from childhood through adulthood is essential if movement is to become a universal habit rather than a medical afterthought.

Policy: Health systems must begin to reward prevention. Insurance providers should recognize and cover structured exercise interventions, rehabilitation through movement, and community-based fitness programs as legitimate, evidence-based treatments. Governments should integrate physical activity goals into national health strategies, monitor population movement levels, and include physical activity metrics in public health reporting. Policies that incentivize walking, cycling, and active commuting, for example through tax benefits or employer wellness programs, can make healthy behavior the default choice rather than the difficult one.

Infrastructure: Cities must prioritize walkability, cycling networks, and accessible recreational spaces as essential public health investments, not optional amenities. Urban planning that encourages active transport, outdoor recreation, and equitable access to green space can dramatically improve both physical and mental health outcomes. Safe, well-lit streets, interconnected paths, and public transport systems that favor active travel empower entire populations to move more naturally. By designing communities around movement, societies can create environments that sustain wellbeing.

Culture: Society must redefine exercise. It should no longer be viewed as a pastime for the motivated few but as a universal determinant of health, relevant to every stage of life and every community. Media, workplaces, and educational institutions all play a role in normalizing movement, celebrating it not only as fitness but as joy, connection, and resilience. When cultures value movement as deeply as they value medicine, health becomes not just a policy goal but a shared way of living.

Rediscovering the Oldest Medicine

The most powerful form of medicine has existed since the dawn of humanity. It requires no prescription pad, no dosage chart, and no pharmaceutical patent. Yet its potential remains vastly underused.

Physical activity can prevent disease, restore health, and extend life expectancy. It is both individual and collective, personal and political. To harness its full potential, the world must move beyond rhetoric and embed exercise into every level of healthcare and public policy.

A future where doctors prescribe movement, where cities are built for walking, and where activity is seen as a human right rather than a privilege is within reach. The question is not whether exercise works, but whether we can reshape how we value it. When activity is woven into the systems that shape our choices, health stops being reactive and becomes a shared cultural habit.

If physical activity could be packaged in a pill, it would be the single most widely prescribed and beneficial medicine in the nation.

~ Dr Robert Butler (founding director of the U.S. National Institute on Aging)

Sources

• World Health Organization (2022): Physical activity – A global public health problem

• British Heart Foundation (2017): Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Report

• American Journal of Health Promotion (2025): Inadequate Aerobic Physical Activity and Healthcare Expenditures in the United States: An Updated Cost Estimate

• The Lancet Global Health (2023): The cost of inaction on physical inactivity to public health-care systems: a population-attributable fraction analysis

• World Health Organization (2020). Physical Activity: Be Active Campaign. WHO

• Pearce, M. et al. (2022). “Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Meta-Analysis.” JAMA Psychiatry. PubMed

• Morres, I. et al. (2020). “Physical Activity and Depression: Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health

• British Medical Journal (2013): Naci, H. & Ioannidis, J.P.A. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes

• Circulation (2016): Anderson, L. et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease

• American College of Sports Medicine: Exercise is Medicine Initiative

• Government of Finland (2019): Physical Activity Prescription Programme

• Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine (UK): Moving Medicine – Physical Activity in Clinical Practice

• Health Promotion Board (Singapore, 2023): National Steps Challenge – Annual Report

• Frontiers in Psychology (2023): A Meta-analysis of the Relationship Between Social Support and Physical Activity

• JMIR Aging (2024): Digital Peer-Supported App Intervention to Promote Physical Activity Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

• Dr. Robert N. Butler: Founding Director, U.S. National Institute on Aging – quoted widely in public health literature

Stay Inspired

Get fresh design insights, articles, and resources delivered straight to your inbox.

Latest Insights

Stay Inspired

Get fresh design insights, articles, and resources delivered straight to your inbox.